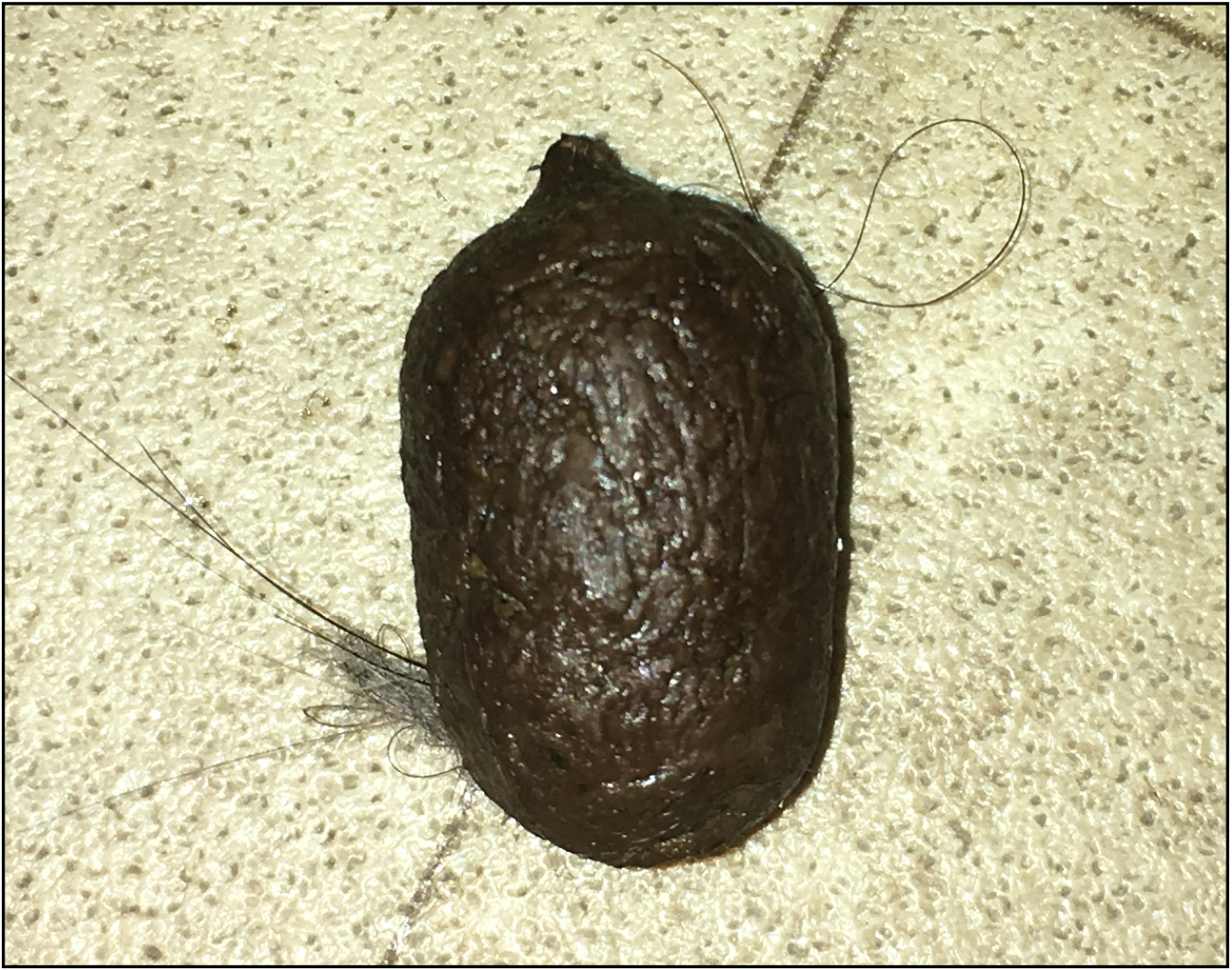

In late January of last year, i encountered the bout of matter (in the most quotidian of places) that would later reemerge in most, if not all, of my academic ventures for the coming year: the moist, brown, plump, smelly-and-elusive, rotund, robust, and deathly, the heterogenous, fecund, warm, visceral, hard-and-heavy, opaque and compact; the cat feces languished in the corner of my living room. perhaps i’d forgotten to take out the litter this week. Or fed her twice over one forgotten, but had meal. i looked into the litter box, only to see a slight accumulation—not enough to induce feline rage or resistance. Liam peaks around the corner, pauses to crouch, then jumps on it, exerting her paws to volley the fecal orb towards next. It catches on the frame of the sliding door and she knocks it away, only for it to end up in the corner adjacent, cradled by the vertex, fixed in place by the right angle, soiling the white, perfect moulding.

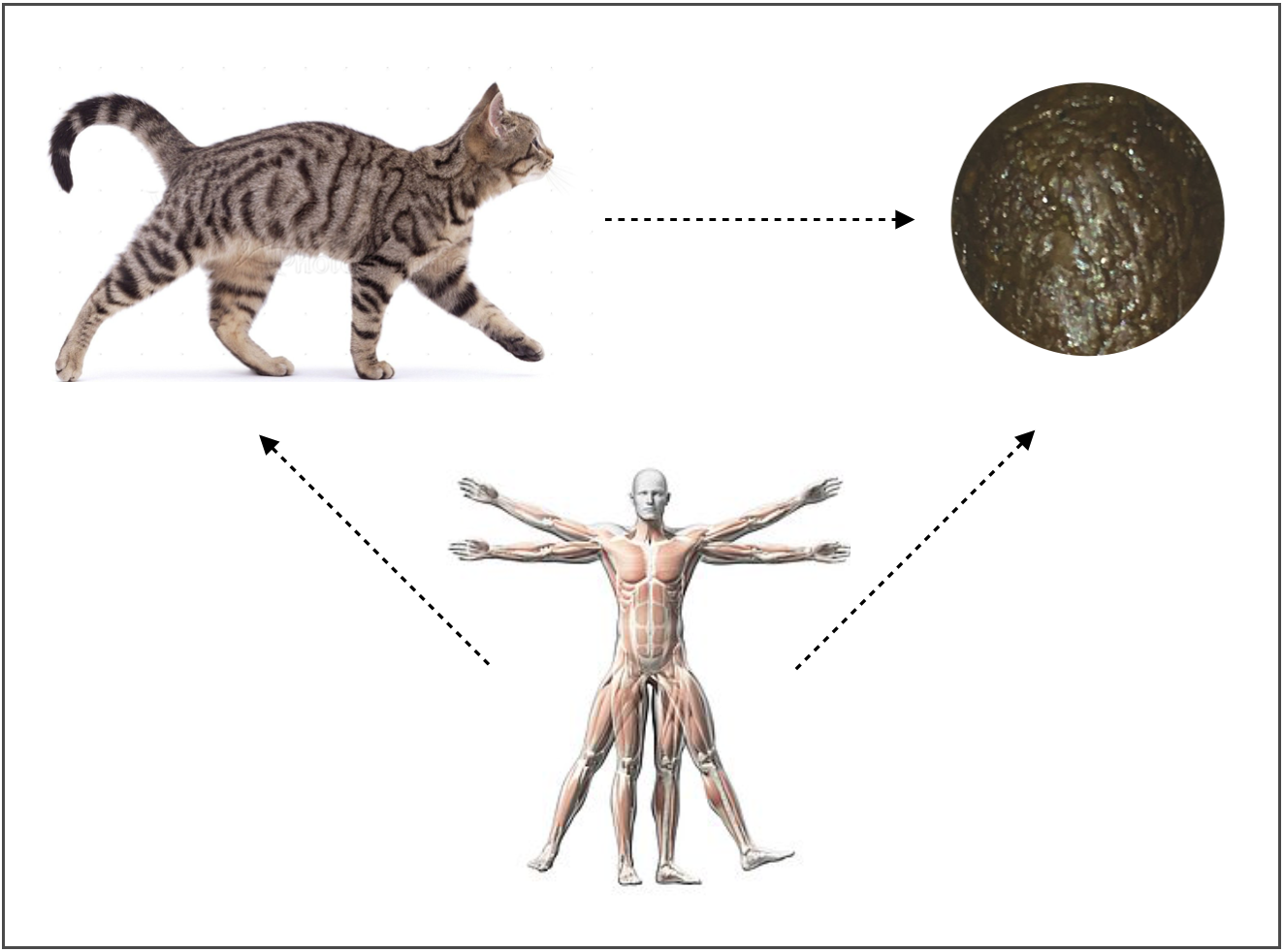

As i jumped in between Liam and her feces to terminate this interaction, i considered our triangulation (see Fig. 2). While the cat navigates her relation to the fece via intertwining material and psychic acts of observing, crouching, pouncing, swatting and obsessing, i must, as my own person with biosociological aversions to fecal matter, learn or attempt to contend with the abject encounter; as such fecal play unfolds, i observe the cat as she exhibits an uninhibited capacity to engage with the adverse stuff, an act of such diligent defiance, refusal or neglect that simultaneously stuns, horrifies and intrigues the onlooker. in this paper, i shall attempt to reckon with this fecund interaction as it constitutes under two subjectivities: one, the cat as she exercises a qualitative negation and conceptual suspension of the fecal object in the mind, effectively establishing it as an exceptional object that sustains a psychically consumptive value, and two, myself, as i consider its unruly constitution while attempting to apprehend the forces that enable cat and cat-feces interplay.

i look to a hermeneutics for peering into this phenomenon in observing the cat’s behaviors as she relates to a rotund presence of cat feces in the advent of fecal play (and while there is, surely, an empirical basis to this program, i want to foreground a subjective experience in this theory-making). The site of this peculiar propensity might be designated in the feline gaze, which combines with a cat’s “silent gait, laser-like focus, keen senses, and flexible body structure” as she readies herself to pounce and capture the fecal object (10). i am focused on the premise of “laser-like focus,” here, as it regards the obsessed, object-oriented attention of the cat-at-play in the attempt to “[grasp] the real and relate to it” (7). Therefore my approach to the interaction of fecal play, for now, shall aim to consider the ways in which feline acts of comprehension pursue, grasp, and embolden the fecal orb as it is conceptualized by the mind. We might start our analysis, then, with Burke’s theses of Astonishment:

“Astonishment,” as Burke writes, is “the passion caused by the great and the sublime in nature, when those causes operate most powerfully” and “that state of the soul, in which all its motions are suspended, with some degree of horror,” in which “the mind is so entirely filled with its object, that it cannot entertain another” (4).

As for this particular section, i am focused on the latter thesis, in which Burke’s describing the “suspension” of the “mind…so entirely filled with its object” might refer to the astonished psyche of the cat as she fixes her gaze on her feces (4). The material acts both cat and feces exert in this interaction—crouching, pouncing, swatting, bouncing, rolling—are bounded by this fixation. They are necessary, for such acts of play induce the urge to fixate, and vise versa. In terms of perceiving such “unstable object[s],” Kristeva designates the act of this fixation as a “speculative cathexis in the abject.” In my stunned, horrified state of conscious, i too, experience such cathexis as i attempt to apprehend this interaction, and the horror yielded by witnessing Liam experience a similar suspension of psychic faculties, yet due/onto the fece itself.

In the advent of fecal play, the cat is both physically and psychically tethered to her feces, unable to entertain any other. As she volleys the fecal orb, alternating left and right paws, her head follows accordingly, fixed on the object as it consumes her comprehension. In this moment, “all motions are suspended,” and all objects, fixed in feline cathexis (4). The fecal object, craddled by the viscous depth-of-field and held in place by a focal hole, does not move in the cat’s frame of perception, as such a suspension of both the soul and the object in mind locks them into a singular positionality. Therefore, in the advent of this attentive play, the cat effectively exceptionalizes the fecal orb, marking it with the stillness and stiffness of a timeless stasis.

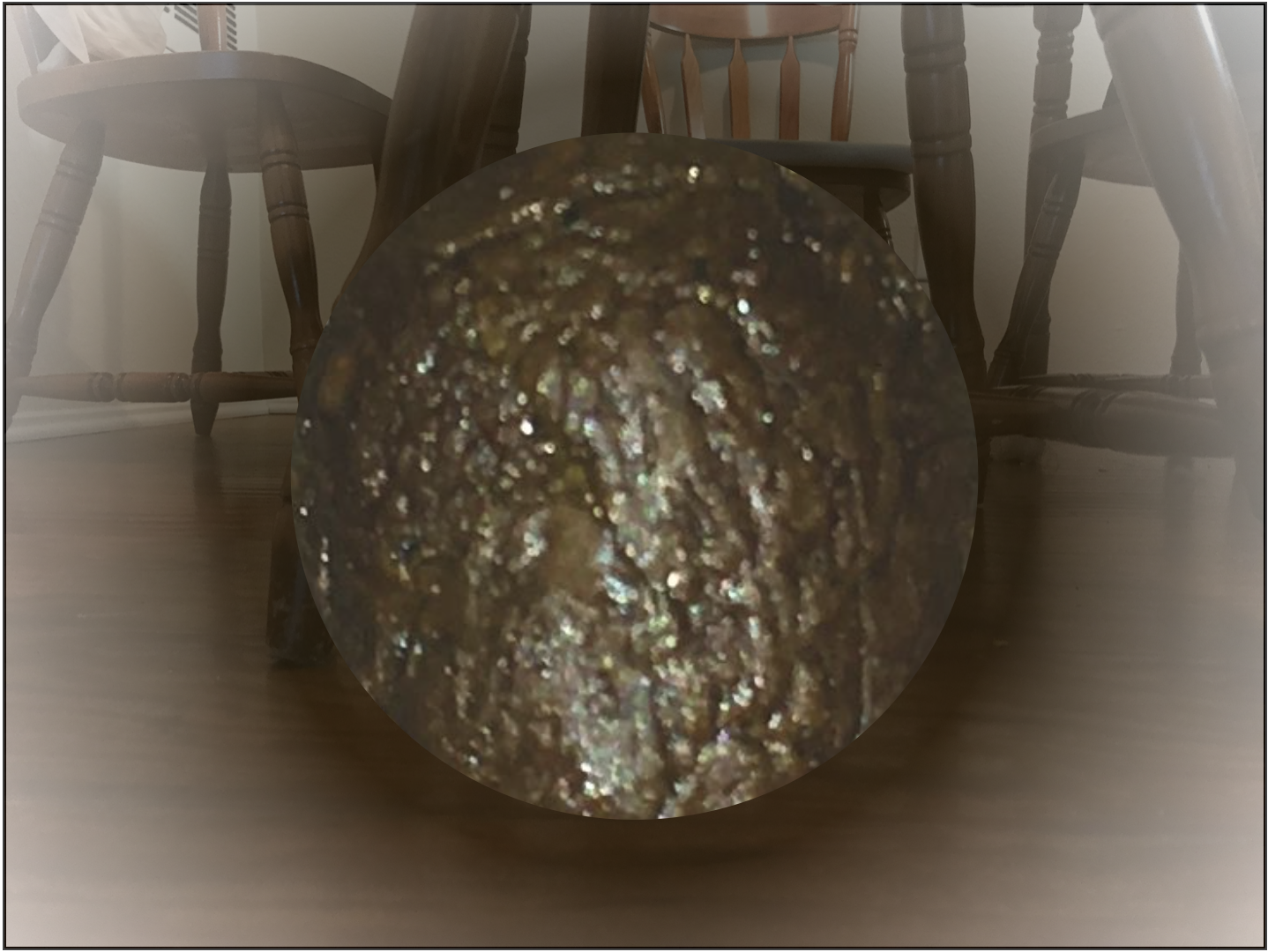

Despite her total fixation on the fecal object, Liam keeps privy to her surroundings, in which the leg of a table or the base of a lamp might intervene, forcing her to align her head, limbs, torso accordingly in an evasive dance. While such obstacles are spatially intrusive, they may be perceptually and psychically accommodated in the fecal pursuit. As shown in Figure 3 (below), obtrusive objects constitute in only the cat’s optic and psychic periphery, whereas the fecal object occupies the center, from which its conceptual presence and occupation encroaches onto and possesses the surround. The cat’s field of comprehension is, thus, dominated by the fecal singularity as it protrudes before her spatial vicinity and constitutes as the sovereign of her attention. The assymetrical divergence between the fece and its obstacle-laden environment, accentuated: the “landscape is merely a backdrop” against which the fecal orb “stands out,” “[pushed]…to the fore” (8).

Yet, it is perhaps, not the material / conceptual totality of the fecal orb that occupies the mind in this manner, as such a condition is, for one, impossible due to the slippages that belie and comprise in comprehension, and for two, cohered by momentary acts of qualitative negation. Qualitative negation (which figures as an intricacy of comprehension) is the process in which the perceiver negates certain qualities of the perceived object as to foreground its others. In this case, the cat sustains the capacity to negate an aversion to toxicity in order to foreground the quality of roundness, thereby psychically transfiguring the fecal object into a ball-play-toy. It is, thus, not so much the foul odor, dirty latency, or promise of infection that occupies the mind, but, rather, the utility of roundness as it enables the fece to roll, and thus, be played with. In exerting qualitative negation, the cat begets the second instance of exceptionalization—where “separate, fixed, and clear-cut” “form takes precedence over matter,” and where “passive, recalcitrant, dark” toxicity is abjected from her conception of the fecal orb, only to leave its perfect, spherical remainder (8).

While our analysis of cat and cat-feces playtime attempts to reveal the processes within that cohere as exceptionalization, it would be remiss to consider this “fecund association” without noting the latent, unexceptionalizing forces at play (6). As it may currently appear that the cat’s fixation on her feces establishes its positionality in the One, the sublime, the singularity, it might be generative to also address the manners in which such a substance constitutes as an unexceptional object—that is, the fece as the many, the quotidian, the commons. In this next section, i revisit my prior speculations in light of unexceptionalization as to recuperate some epistemological gaps, left by our solely exceptionalist approach to understanding cat on cat-fece playtime.

In an encounter with a moving object, it is not uncommon for the cat’s “predatory instincts [to] kick in,” an evolutionary response that excites at the presence of prey (1). For Liam, this urge to touch or capture is, perhaps, an exceptionalizing force, as the object is recognized on the basis of desire. Yet, such cat on cat-feces interaction, as we have seen, requires a physical engagement with the fecal object—swatting, volleying, retrieving—that constitutes, particularly, under touch. In repetitious bursts, the cat touches the fece as she knocks it away, inciting the urge to touch it again; the unexceptionalizing move—the cont[act] of touch—leads to the exceptionalist urge—the desire to touch, and so on. When we attend a gallery space, we are instructively deterred from touching the art, for the value of the object in question is, perhaps, determined by its likeness or equivalence to the original state. If said object is soiled by the touch, its assigned value suffers until mint-condition is restored. If the art is “totaled” by touch, then it is “formally demoted…to mere object-hood… and removed from the market,” sustaining a shift from institutionalized, but precarious, exceptionalism into abject, quotidian unexceptionalism (9). That is because, in the Western tradition, the display of a material artwork (such as painting or sculpture) signals an intent of completion, whereas the disruption/obstruction of display evokes incompletion, compromise, or complication.

Yet, we need not imbibe Western methods of valuation when observing cat on cat-feces playtime as a condition that qualifies the fece as a work of art. Such a logic should only apply if we validate that the fecal orb, as an artwork, was completed prior to fecal play—at the instance it was excreted by the feline anus and exposed to a space of display (the litter box, or, on rare occasion, the living room). Conversely, if we validate that the advent of the originary does not, in fact, mark the completion of an artwork, then the fece’s constitution as such must also enfold the indefinite processes that follow; the art relinquishes the static project of being, and moves into an ontology of becoming. Therefore, the conditions that qualify the fece as an artwork, as in the Chinese tradition of landscape painting (and its economic and pedagogical circulation), are “subject to continual change and permanent transcription” (7). In the case of cat and cat-feces interplay, this transcription figures as paw prints on the de/reformed surface of the fece as she handles it, marring its original, ‘completed’ state by accumulating haptic latencies. A state of completion, then, in this sense, does not determine the state of Art, or, more aptly, the Art state. For it is continual change rendered by a history of re/incompletions that enfolds in the fecal orb’s ultimate constitution as an artwork: “it is not static. Rather, it is fluid” (7).

footnotes:

¹ While i am both privy and indebted to the bevy of discourses (Black studies, new materialism, posthumanism) that foreground the vibrancy of matter, and thus, the agency of the ‘object’ as the notion destabilizes our conception of human subjectivities, it is pertinent that i make the subject-object distinction as to realize this triangulation—the cat, the feces, myself—in the context of unexceptional art, as such a project requires us to acknowledge the reciprocity between the viewer and the viewed, or, in this case, a work of art. although these early ramblings, perhaps, tend to fetishize the object and potentially dismiss its epistemological agencies (the stuff about it that might inform, inflect, or contaminate our anthropo-cognitions), i shall attempt to reconcile the flaccidity in the finishing analyses, with which we shall venture into the infinitely complicated mattering of cat feces as it implicates the-world-at-large. but for now, i temporarily revoke the aspiration to vitalize, sympathize and defetishize the object, as the coherence of our critique requires the elitist, capitalistic, and anthropocentric gaze that constitutes the viewing of Art in the first place.

² See Adorno’s Negative Dialectics, in which he proposes that “objects do not go into their concepts without leaving a remainder” (2). Adorno effectively calls this remainder—this stuff—that eludes processes of comprehension / conceptualization the “nonidentity” (2).

³ Particularly toxoplasmosis (toxoplasma gondii), a parasite cats “may shed… in their feces for 7-21 days the first time they get infected” (3). Toxoplasmosis is known to “infect people as well as birds and other animals” (3).

⁴ Yet, utility is, perhaps, a most unexceptionalizing condition, for exceptionalist principles that embolden art as Art do not necessitate it to be functional, pragmatic or useful in a utilitarian sense.

✿ 2020 steven chen w/ Liam

works cited:

(1) Anderson, Jason. “Why Are Cats Attracted to Small Moving Objects?” Quora, 15 May 2019, www.quora.com/Why-are-cats-attracted-to-small-moving-objects.

(2) Adorno, Theodor W., and E. B. Ashton. Negative Dialectics. The Seabury Press, 1979.

(3) Anonymous, “Toxoplasmosis and Cats.” Pets & Parasites by CAPC, www.petsandparasites.org/resources/toxoplasmosis-and-cats.

(4) Burke, Edmund. A Philosophical Enquiry Into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful. Wentworth Press, 2016.

(5) Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. London: Athlone Press, 1988.

(6) Gourgouris, Stathis. Does Literature Think?: Literature as Theory for an Antimythical Era. Stanford University Press, 2003.

(7) Han, Byung-Chul. Shanzhai: Deconstruction in Chinese. Translated by Philippa Hurd, The MIT Press, 2017.

(8) Julien, François. The Impossible Nude: Chinese Art and Western Aesthetics. University of Chicago Press, 2007.

(9) Lerner, Ben. 10:04: a Novel. Picador, 2015.

(10) LLC, Aquanta. “Why Do Cats Stalk Things?” Home, www.cathealth.com/behavior/how-and-why/1214-cat-stalking.

/december 2019